For some time it has been possible to portray the Transatlantic divide on the basis of three concepts: God, arms and the law. Now, the breach between them has also become a domestic issue in the US. Formerly Europe was less religious than the US and religion had less bearing on its domestic and foreign affairs, it was less inclined to use force and more supportive of multilateralism based on the law. Matters have changed. Today, polls conducted by the Pew Center show that while Americans are less religious, religiosity has become more radical and more influential among Republicans; the support of the Christian right (represented by vice-president Pence) is crucial to the Republican Party, even though Trump is not one of them, whereas the Democrats are less fervent believers. On the question of arms, the last two Presidents (Obama and Trump) have had little appetite for armed intervention abroad, although the US wants to maintain its military supremacy. But the issue of the citizens’ right to bear arms –gun control– now divides Democrats and Republicans more than ever. As far as the law is concerned, international law –which did so much to foster US development in its day– has been in crisis since before Trump, and Trump has aggravated it. Existing treaties are disavowed and no significant new ones are signed. But this also has an internal dimension, with a Supreme Court firmly controlled by those who sympathise with Republican values, by six to three with the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, an advocate of ‘textualism’ or ‘originalism’, and of a radical Christian stripe. The Trump Administration’s appointment of judges for life at all levels of the judiciary has been striking. Biden wants to find a consensus to review the system.

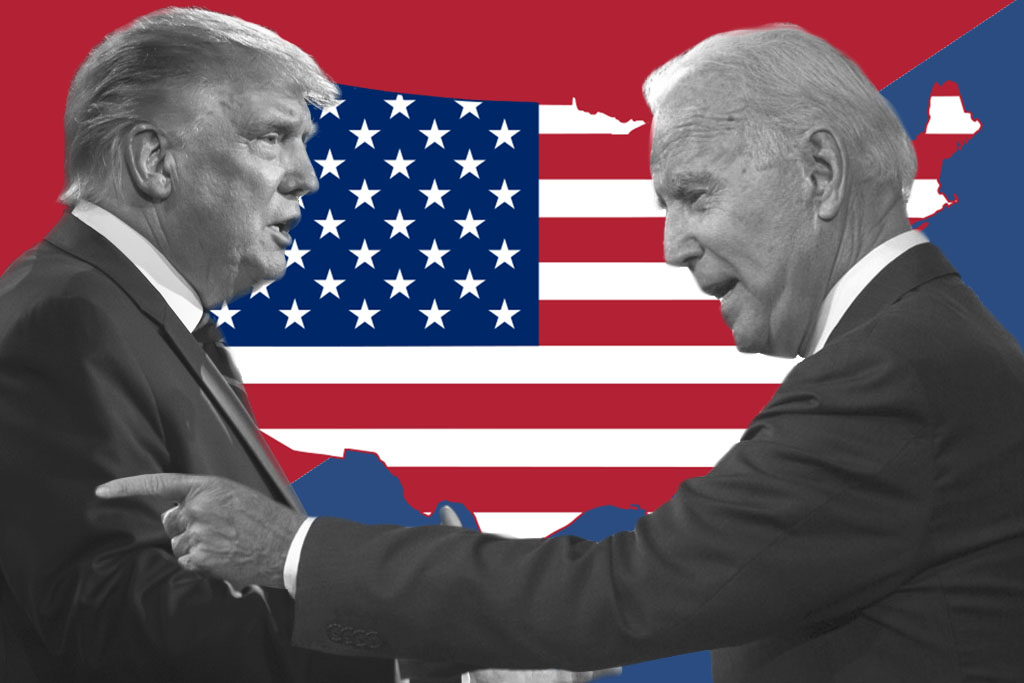

‘God, arms and the law’ thus signifies a profound breach that is no longer transatlantic but an unprecedented polarisation within US society and politics. If Trump wins a second term, in the electoral college or the Supreme Court (he will lose the popular vote), the breach will only widen. John Bolton, Trump’s former National Security Advisor, argues in his book that in a second term the President will be ‘far less constrained by politics than he was in a first term’. If he wins, he is set to become a more disruptive President, for the US and for the world, than he has been until now. Trump will not hesitate to divide –the US and the world– whereas Biden will seek to reunify. But he cannot and will not by resorting to former assumptions, domestic or international, that have to a large extent been rendered obsolete.

Biden will prioritise the pandemic, the economy and domestic policy, in order to bridge the internal gulf prior to the external one. He knows that if he wins he will owe it, in no small measure, to the votes of Republicans who do not see themselves reflected in Trump. If he is to govern with ease, Biden needs the Democrats not only to retain the House of Representatives but also to win the Senate, currently in Republican hands, and even to secure 60 seats to prevent opposition filibustering from thwarting major legislation. This is no easy task. The profound polarisation within the US will shackle his foreign policy.

How does this affect the Europeans? The US has changed, China too, and the world has shifted. As Sylvie Kauffmann points out, ‘those who see Joe Biden as a reliable ally in foreign policy run the risk of a rude awakening’. If Trump wins, he will stick to his idea and policy of ‘America First’, of extreme US exceptionalism partly based on religious sentiment and the notion of a chosen people. Trump will take a harder line on Europe, on trade, in his opposition to the idea of ‘European sovereignty’, or even of ‘open strategic autonomy’, as well as in the technological domain, and in his standoff with China. A question mark will remain over NATO, with Europe still not having the resources to make such autonomy manifest. Paradoxically perhaps it will promote it. All this when the West –if such an expression can still be used– is losing influence in the world, a phenomenon that will persist with Biden, these being deep-seated changes.

On the question of China, barring minor tweaks, Biden seems unlikely to steer a markedly different course. The US, and in particular the world of Washington –referred to (by the Obama Administration) as the establishment foreign policy ‘blob’, including the influential think tanks– has shifted on the issue and has mobilised against China. Both Republicans and Democrats see China as the greatest contemporary threat, perhaps the only one, to the preservation of US global power. The so-called Cold War 2.0 between the US and China is going to be Trump’s main foreign legacy. With him, or in opposition to him, Europe may be more inclined to seek its own path in relations with China, the ‘Sinatra Doctrine’ (‘My Way’) alluded to by the High Representative Josep Borrell. Although it may seem paradoxical, things will be more difficult for Europe with Biden, because it will want to ingratiate itself with him in this and other areas (perhaps not on greater European military spending, an idea that has also taken root in Washington). Biden will restore the diplomatic machinery (and that of the intelligence services), decimated by Trump, and put good relations with democratic allies before autocrats. He will also herald some reversion to multilateralism, including that of the World Health Organisation (WHO), from which Trump has withdrawn the US, and try to restore a degree of nuclear understanding with Iran. He will base himself on the four Ds: the domestic, as a priority; deterrence of China and Russia; support for democracy, as Anne Marie Slaughter argues; and diplomacy too may be added to the list.

Something that may bring Washington and Brussels closer together is that the Democrats, like growing numbers of European governments and institutions, are increasingly in favour of reining in the size and power of big tech companies in the US, as has been made apparent by the House of Representatives, and the case pursued by the Department of Justice against Google. Perhaps the issue where the Europeans and Americans (and even the Chinese) converge most, however, under a possible Biden presidency is the fight against climate change, if the US reverts to the Paris accord. Will carbon enable the internal and external rifts of ‘God, arms and the law’ to be bridged (if Biden wins) or will they be aggravated (if Trump wins)?